When I first moved into my first home after converting to Islam, a dear friend of mine bought me a bottle of vinegar. He shared with me that the Beloved Prophet Muhammad ﷺ had taught that vinegar was the condiment of the Prophets and that no house will ever fall into poverty where there is vinegar. Since that moment, it became my custom to purchase a bottle of vinegar whenever I moved into a new home, and I'm quite certain I'm not alone.

Over the years, that teaching stayed with me. However, only recently have I come to realize that keeping vinegar is not mere superstition—a devotional act in imitation of our Beloved Prophet—but rather at the very foundation of our understanding of economics.

Vinegar has been a staple in human civilization for millennia. Its origins trace back to ancient Babylon around 5000 BCE, where it was produced from dates and figs for both medicinal and culinary purposes. Archeological records show that the Ancient Egyptians have been using vinegar since at least 3000 BCE. Furthermore, vinegar production was well-established during the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE), with records indicating that royal households employed dedicated vinegar makers.

A versatile liquid primarily composed of acetic acid and water, vinegar is the result of the fermentation process of ethanol alcohol by the acetobacter microorganism. The fermentation process can include fruits, grains, and other alcoholic base ingredients leading to different vinegar bases with unique flavour profiles and applications. The process starts when wild yeasts convert sugars present in the base ingredient into alcohol. When exposed to oxygen, the acetic acetobacter further ferments the ethanol into vinegar, which gives it its distinctive sour taste and pungent aroma.

Those familiar with the Islamic legal tradition will notice the use of alcohol in this process, which is considered prohibited to use. Vinegar must come from alcohol. Scholars have discussed this transformation as one of purification, called taḥawwul ṣaḥīḥ.

“The vinegar that is produced through a taḥawwul ṣaḥīḥ will not only be a high-quality vinegar but it is also guaranteed to be ḥalālan ṭayyiban and free from alcohol.”1

Interestingly, according to Islamic law, the sale and trade of alcohol is also strictly prohibited, whereas vinegar is not. Making vinegar requires turning sugars into alcohol, meaning that the vinegar maker, in an Islamic context, must produce their own alcohol, because purchasing it would be prohibited. Given that limitation, it would seem that the production of vinegar would have been a cottage industry or a small-scale commercial production. And perhaps herein lies the prophetic wisdom of a household with vinegar which will not taste poverty.

Making vinegar at home is an embodiment of frugality and home economics. It is the process of using fruit scraps (e.g. apple cores and peels, citrus peels, pineapple skins and cores, pear scraps, grape skins and pulps, stone fruit pits and skins, berry mash, mango peels and pits, banana peels, melon rinds, and so on). Before sending them out to compost, the sugars and wild yeasts in those scraps are used to prepare vinegar.

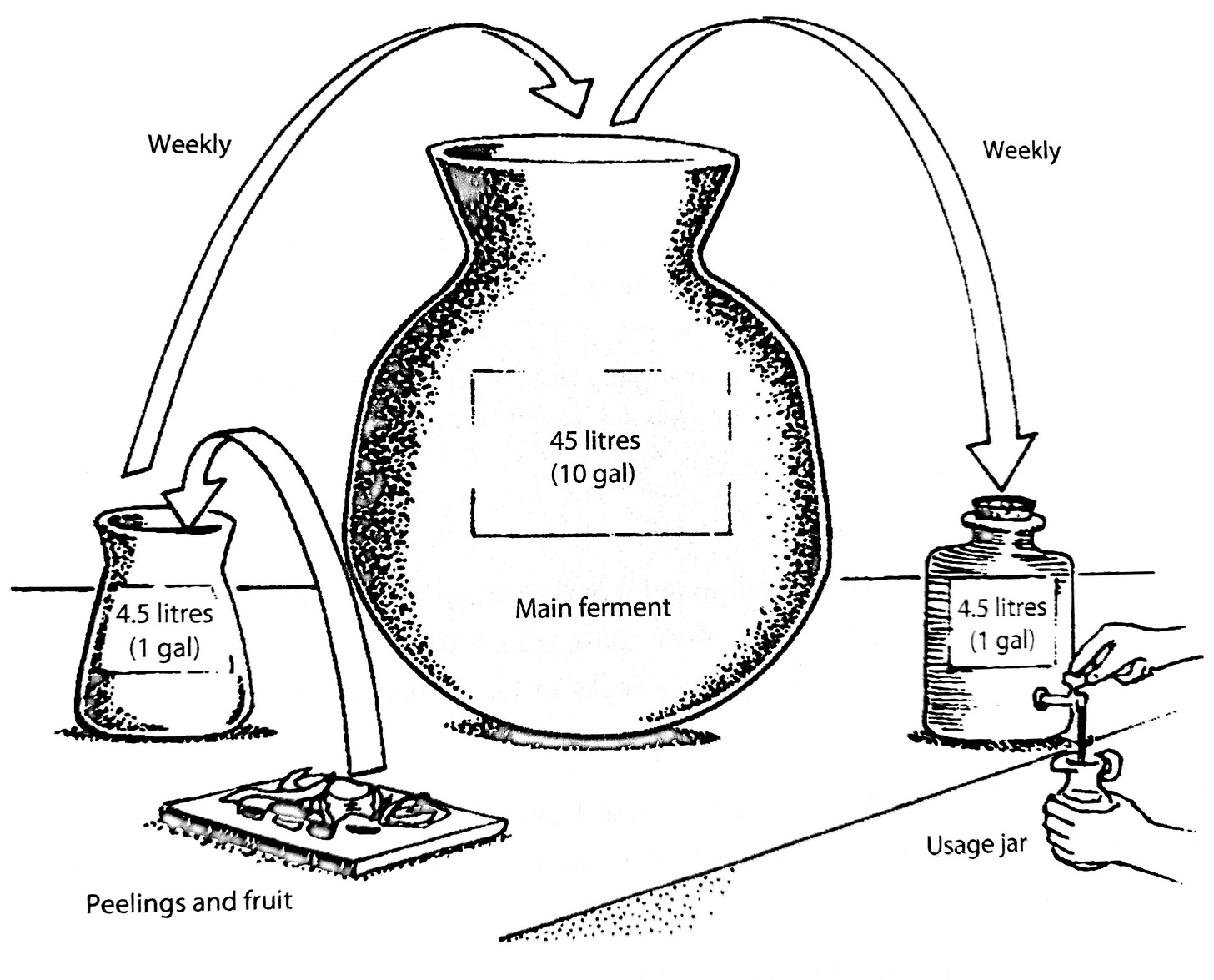

Any home kitchen can start making vinegar. In The Permaculture Book of Ferment and Human Nutrition, Bill Mollison presents a simple method to make this basic acetic or tartaric acid solution. His method is as follows: To make vinegar, combine fruit peels with lukewarm water and a small amount of unpasteurized vinegar or beet juice. Cover with a muslin cloth and leave in a warm place for two to three weeks, stirring occasionally. Strain, bottle, and store. Once you’ve made vinegar, you can establish a continuous process with three containers.2

Understanding this basic process is fundamental to our relationship with food, nutrition and waste. Economics begins in the home, and the home’s industry is the kitchen. Unfortunately, our lives have become devoid of frugality. We live with an illusion of abundance. Yet this illusion engenders a scarce dog-eat-dog world. Ironically, a frugal home practices gift economics. By seeing the use of things, one cultivates a deep sense of gratitude. Again, no coincidence that the Quran promises us, “If you show thanks, I swear to increase you.” (Quran, 14:7) Our abodes can be beacons of gratitude and the starting point for a truly regenerative culture.

Harahap, I., Shukri, A.S.M., Jamaludin, M.A., Nawawi, N., Alias, R., & Zaharim, A. (2020). The application of taḥawwul (transformation) process for determination of vinegar status in the Malaysia market. Food Research, 4(3), 896–905. https://doi.org/10.26656/fr.2017.4(3).393. Note that this is article is not a discussion on the permissibility of vinegar and/or alcohol according to Islamic law. We are looking at the folkloric use of vinegar as a basis of the management of the household (economics).

Mollison, Bill. The Permaculture Book of Ferment and Human Nutrition. Tyalgum, Australia: Tagari Publications, 1993. p.11

I love vinegar. I use apple vinegar.