#Seed029: The Metacrisis Epoch

Diagnosing and overcoming our global civilization's pivotal moment

The Industrial Age has reached its zenith and our civilization is suspended mid-air, waiting for an eventual fall. In the meantime, artificial intelligence is presenting itself as perhaps an even greater faustian bargain than when we tapped into the power of fossil energy. This crisis is unprecedented. Never before has humanity been so globally interconnected, intertwined, and interdependent that a failure in the global system would impact all of humanity.

Some philosophers are calling this moment, the metacrisis. The metacrisis is “the historically specific threat to truth, beauty, and goodness caused by our persistent misunderstanding, misvaluing, and misappropriating of reality.”1 The metacrisis is the underlying diagnosis of the many crises that plague our global civilization. Rather than segmenting crises and assuming distinct solutions for each, it's crucial to acknowledge their interconnectedness and the global impact they all have.

By definition, the Greeks perceived crisis (κρίσις) as the pivotal moment signifying either the onset of recovery or the inevitability of death in a patient. Applied to systems, this is the turning point on whether a system will self-regulate or collapse. Our human civilization is facing many crises in its subsystems (e.g. economic, social, environmental, political) but as a whole, it is the underlying metacrisis that will determine its flourishing or collapse. The scale of our civilization uncovers its vulnerability. One just needs to look at the impact that the Covid-19 lockdowns in China had on the global supply chain.2 To understand this pivotal moment, we need to provide a proper diagnosis. The Hippocratic diagnosis framework is fitting and can be summed up as follows:

Predictable progression: Illnesses (or dis-ease) normally run a certain course (and can therefore be predicted);

Environmental determinants: Their origins are connected to geographic and atmospheric factors; and

Modal modification: To recover his health, the patient must modify his ordinary mode of living.3

This essay will explore how this framework helps us better grasp the metacrisis by presenting a brief overview of how complex systems collapse. We will attempt to explore the metacrisis in terms predictable progression and environmental determinants. This will in turn help us diagnose the metacrisis. We will then take a deeper dive into how community development (in particular the establishment of bioregional intentional communities grounded in the spiritual, physical, social, and psychological dimensions of human existence) is the only possible path towards some sort of recovery from the metacrisis. This essay isn’t meant to be exhaustive, but rather we hope that we find a way to set a direction towards the recovery of human nature.

Predictable Progression

Let’s assume that all complex systems normally run a certain course (and can therefore be predicted). I understand that this generalization has exceptions. Nevertheless, the generalization generally holds true, in our day-to-day lives. Systems are predictable, and there are valid predictions that we can make about them. All men are mortal is a prediction about a system (human beings) and its eventual failure. All men will get sick is another prediction, perhaps not as universal, because some men may not get sick, nevertheless most if not all men will get sick in some way, is a valid assumption. All systems will collapse. That is predictable. But not all systems will collapse in the same way. The way in which a system regulates or manages that collapse determines its ability to recover or not. In other words, all systems will face a crisis.

Take for example a forest that has recently been hit by wildfires. Pioneer plants will begin to cover the soil, serving as a protective scab to the earth’s open wound. These pioneer plants, often nitrogen fixers, fertilize and protect the soil from the harsh sun, creating a microclimate that allows for a secondary growth of new species. This succession will then give way to another set of species, who serves as protectors for newly established tree saplings. This process slowly restores the forest. Though the forest system collapsed, a new forest system emerged.

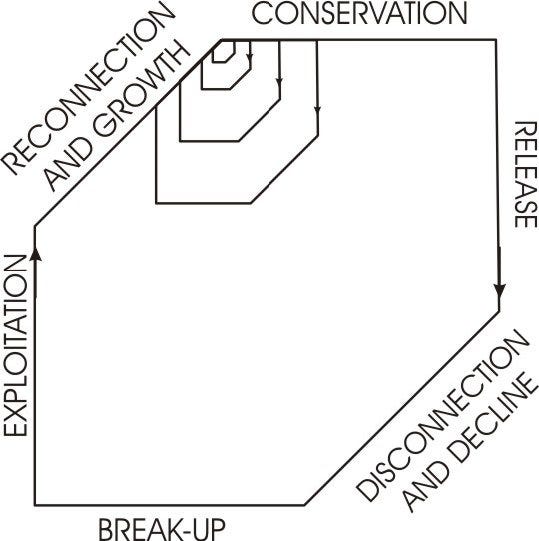

This process can be represented by the adaptive cycle of resilient systems. Systems theorists, C.S. Holling and Lance Gunderson, modelled the adaptive cycle of resilient systems into four phases: exploitation, conservation, release, and reorganization. Complex systems, regardless of scale, function in this cycle.

The critical moment, which we are calling a crisis is found somewhere during the release phase of the cycle, ultimately deciding whether a system collapses completely (and thus lose all potential) or reorganizes and is built up again. Systems collapse all the time; creatures die, civilizations crumble, stars burn out their fuel supply. But complex systems reemerge from fallen ones; forests after wildfires, civilizations from the ruins of empire, etc. This is why the Earth has witnessed many systems collapse over its history, yet still lives on. The question isn’t whether or not we can prevent a system from collapsing but rather how do we ensure that systems can reemerge. Through predictable progression, we not only start understanding the cycle of systems but also identifying the nature of the crisis they face.

Ibn Khaldūn’s theory of asabiyyah (Arabic for group cohesion, shared purpose) provides a coherent view of the predictable progression of civilizations4 which remains relevant to this day. The stages are as follows:

Early Tribal Stage: strong asabiyyah, usually through blood relatives, is needed due to austere conditions. This is the start of the exploitation stage of the adaptive cycle.

Expansionist Phase: strengthened asabiyyah ultimately forming empires (or increasing complex social systems) through the conquest of lands and resources. In this progression, the exploitation stage is moving into the conservation stage.

Decadent Phase: a civilization’s contact with diverse cultures introduces luxuries, leading to a shift towards comfort-seeking and sensual gratification. Traditional values and mores begin to wane, weakening asabiyyah. This is the end of the conservation phase.

Senile Stage: asabiyyah has completely dissappeared and there is no more shared purpose. The system is no longer able to sustain itself and becomes vulnerable to internal and external pressures. This is the release phase of the adaptive cycle trigerring the collapse of civilization.5

It is clear that we find ourselves in the decadent phase of our global civilization. The post-WWII world gradually weakened asabiyyah, bringing the global civilization into a decadent phase for a few decades. Our energy use and consumption rates has been exponentially skyrocketing6. Alongside, families and sexual mores continue to erode7. Since the rise of social media, the senile stage is exemplified by the increasing political and moral polarization8, where our families, neighbours, and co-citizens are seen as political opponents. The rampant individualism that characterized our world since WWII slowly weakened our civilization’s asabiyyah.

Environmental determinants

To gain a deeper insight into the metacrisis, we must closely examine the environmental conditions of its encompassing ecosystem or ecological system. Let’s start with a simple definition. The term ecosystem first appeared in print in 1935, coined by Arthur Tansley after seeking a term from his colleague Arthur Roy Clapham that would encapsulate “the physical and biological components of an environment considered together as a unified whole.” The term ecosystem is a portmanteau derived from two Greek words: οἶκος (oikos), meaning home, and σύστημα (systēma), meaning organized system. I propose we start defining ecosystem or ecological system as the complex organization of our home.

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory (see Figure 2 below) posits that an individual part within a system is influenced by a series of interconnected systems (microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, chronosystem). In human ecosystems, this ranges from the immediate surroundings (family, neighbors, friends) to broader societal structures (culture, social mores). Applying this theory to the metacrisis can use us identify the multiple levels at which crises occur and interact, while emphasizing the interconnectedness of individual actions, societal structures, and global process. In other words, we not only begin to paint a picture of the environmental determinants of the metacrisis but also how the metacrisis is experience at an individual level.

That metacrisis acknowledges that there are many crises happening at once. However, each crisis is simply a symptom of something more fundamental. We could say that particular crises help us better understand the environmental determinants of the metacrisis. Crises at the chronosystem level involve shifts over time that have widespread impacts on society and individuals, often reflecting accumulated effects of policies, technologies, and societal behaviors. For example, both the energy and climate crises are direct results of industrialization and the historical reliance on cheap fossil fuels. The macrosystem encompasses cultural, economic, social, and political ideologies and structures that influence societal responses to crises. The widening gap between the rich and the pool, exacerbated by global economic policies favoring the accumulation of wealth is an example of a crisis at the macrosystem level. Exosystem-level crises affect individuals indirectly, through larger societal systems and structures. An overloaded healthcare system due to an ageing population is an example of this. Crises at the mesosystem level emerge from the interactions between different subsystems, affecting the networks that support individuals. The housing crisis, for example, affects the interconnected systems of not just the home, but also school, work, disrupting social support networks and compounding stress and trauma for individuals. And finally, microsystem crises are directly experienced by individuals in their immediate environments and relationships. The family crisis due to divorce, separation, financial stress, or other relational conflicts, can have a profound and direct impact on the individuals within that unit, especially children.

The list of crises mentioned above is just the tip of the iceberg. What they reveal is that these are the spirit of the times. Jonathan Rowson writes that “we don’t quite know what crisis is asking of us, and because the world is not now changing as it needs to – mind and society are not moving with the spirit of the times.”9 In other words, the metacrisis stems from our disconnection from the essential human questions which bring meaning to our lives.

Modal Modification

Our global civilization has reached a state of moral entropy. As William Ophuls writes, “[i]n civilizations, change is incessant. This exposes morals, mores, and morale to a continuous undertow of entropy. Hence the moral core of the society erodes until vigor and virtue have been entirely displaced by decadence and decay.”10 The metacrisis is a crisis of human nature, underpinning the Quranic dictum, “do not spread corruption on the earth.” To recover from the metacrisis, we must modify our ordinary mode of living. his health, the patient must modify his ordinary mode of living. We need a civilizational modal modification. Every system has subsystems. Though a larger system may collapse, a subsystem can essentially survive that collapse. As David Fleming explains, the subsystem has greater flexibility than larger systems because it operates on “a shorter life-cycle than the overall system.” He continues, “when repeated many times by many parts of the system, this series of small-scale new beginnings can provide a community or civilisation with constantly-renewing resilience. The more flexible its subsystems, the longer the expected life of the system as a whole.”11

Returning to the adaptive cycle of resilient systems, we find that systems collapse after the conservation phase. Complex systems are resilient when they are integrated with subsystems. Subsystems allow for smaller scale releases to return to the exploitation phase (or as Fleming defines it the reconnection and growth phase, see figure 3).

Modal modification boils down to integrating human-scale subsystem within the larger global system. Of course, this increases the complexity of the global system, but it doesn’t necessarily increase its size. Rather it increases its resilience fostering what Christopher Alexander calls a mosaic of subcultures. “A person will only be able to find his own self, and threfore to develop a strong character, if he is in a situation where he receives support for his idiosyncrasies from the people and values which surround him. […] In order to find his own self, he also needs to live in a milieu where the possibility of many different value systems is explicitly recognized and honored. More specifically, he needs a great variety of choices, so that he is not misled about the nature of his own person, can see that there are many kinds of people, and can find those whose values and beliefs correspond most closely to his own.”12 This mosaic of subcultures is nothing but a mosaic of intentional bioregional communities.

The blueprint for a modal modification is one in which human nature is rediscovered. The expansive system of our global civilization has transformed the human being into a bureaucrat—a mere cog in a machine, stripped of meaning and disconnected from nature. Rediscovering our human nature means going beyond the dogmas of modernity (e.g. rationalism, progress, individualism, secularism, scientism) and postmodernity (e.g. skepticism, relativism, nihilism). It means holistically addressing the physical, social, psychological, and spiritual dimensions of human existence. A possible pathway to integrating the dimensions for holistic recovery could be as follows:

Cultivating a collective sense of purpose and connection to the Creator (e.g., something greater than oneself), through religion and spirituality, with the sacred at the center of our lives through prayer, meditation, and ceremony.

Embedding virtue ethics deeply into education, governance, and daily life, emphasizing prudence, wisdom, courage, and justice, while cultivating a culture that values the common good over individual gain, fostering cooperation and mutual support.

Mending the family and extended family through the development of positive sexual mores that recognize the dangers of lust and the community impact of love and marriage.

Revamping education systems to focus not just on academic knowledge but on character development and the skills necessary for resilience (such as emotional intelligence, conflict resolution, etc.).

Shifting the societal focus from individual rights to collective responsibilities.

Creating systems of governance and social interaction that prioritize local needs and capabilities, encouraging participatory decision-making, community ownership of resources, and good governance.

Developing flexible, transparent, and small-scale governance systems capable of responding quickly to emerging challenges and incorporating feedback from community members.

Developing local economies that are less dependent on global supply chains would reduce vulnerability to external shocks, including supporting local agriculture, small businesses, and crafts.

Encouraging the development of shared resources, both digital (like open-source software and information) and physical (such as community gardens and tool libraries), to promote access over ownership and foster a culture of sharing and cooperation.

Redesigning infrastructure to be regenerative and resilient, using renewable energy sources, regenerative materials, and designs that work with, rather than against, natural systems (e.g. biomimicry)

Transitioning to healthcare systems that prioritize holistic well-being, including preventative care, mental health, and the integration of traditional forms of medicine (herbalism, unani medicine, TCM) given the post-collapse access to modern medicine that was dependent on cheap fossil fuels.

Encouraging cultural and participatory artistic expressions that reflect the community's identity and values, celebrating local traditions while being open to new influences and innovations.

Concluding Remarks

No one knows what a global collapse will look like. But we know that such a collapse will inevitably happen. We are living a turning point in history yet we are trying to sustain what William Ophuls calls a Titanic. We are trying to fix a ship that is heading towards a crash. Unfortunately, the global economic system and its champions, driven by greed and envy, are attempting to rectify the harm it has done while growing the economy. The truth is we can’t continue to grow on a finite planet. Until we realize this truth, crises will continue to appear. Nevertheless, we need to start building community ecosystems, grounded in a deep relationship to the Creator (beyond our selfishness) and with a reinvigorated sense of purpose. This is how we will recover from the metacrisis.

See Rowson, Jonathan. Prefixing the World in Perspectiva, Sep. 6 2023. The full definition provided by Rowson is as follows: “The metacrisis is the historically specific threat to truth, beauty, and goodness caused by our persistent misunderstanding, misvaluing, and misappropriating of reality. The metacrisis is the crisis within and between all the world’s major crises, a root cause that is at once singular and plural, a multi-faceted delusion arising from the spiritual and material exhaustion of modernity that permeates the world’s interrelated challenges and manifests institutionally and culturally to the detriment of life on earth.”

Bradsher, Keith. China’s Covid Lockdowns Set to Further Disrupt Global Supply Chains in The New York Times, Mar. 15 2022.

To simplify the process, I’ve summed up the framework in the following tripartite way: predictable progression, environmental determinants, modal modification. For more on Hippocrates and the origins of medicine, see Jones, W.H.S. (1868), Hippocrates Collected Works I, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, retrieved March 20, 2024.

It is worth looking at Peter Turchin’s work on cliodynamics that attempts to identify the patterns underlying why empires rise and fall, why populations and economies boom and bust, and why world religions spread or wither. https://www.nature.com/articles/454034a

This is an excellent piece that applies Ibn Khaldun’s theory on the rise and fall of the Mughal Empire. See Wazir, Asmat & Dawar, Shakirullah & Khan, Hamayun & Khalid, Abda. (2022). Ibn Khaldun’s Theory of Asabiyyah and the Rise and Fall of the Mughals in South Asia. Journal of Al-Tamaddun. 17. 159-169. 10.22452/JAT.vol17no2.12.

Tverberg, Gail. World Energy Consumption Since 1820 in Charts in Our Finite World. Published Mar. 12 2012. Accessed April 4 2024.

Eberstadt, Mary. The New Intolerance in First Things. Published March 2015. Accessed April 4 2024.

Haidt, Jonathan. Politics, Politics, Polarization, and Populism. 2017.

Rowson, Jonathan. Prefixing the World in Perspectiva, Sep. 6 2023.

Ophuls, William. Immoderate Greatness: Why Civilizations Fail. CreateSpace, North Charleston, SC. 2012. p.59

Fleming, David. The Wheel of Life in Lean Logic: A dictionary for the future and how to survive it. Accessed Apr. 3 2024.

Alexander, Christopher et al. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. Oxford University Press, New York. 1977. p.48