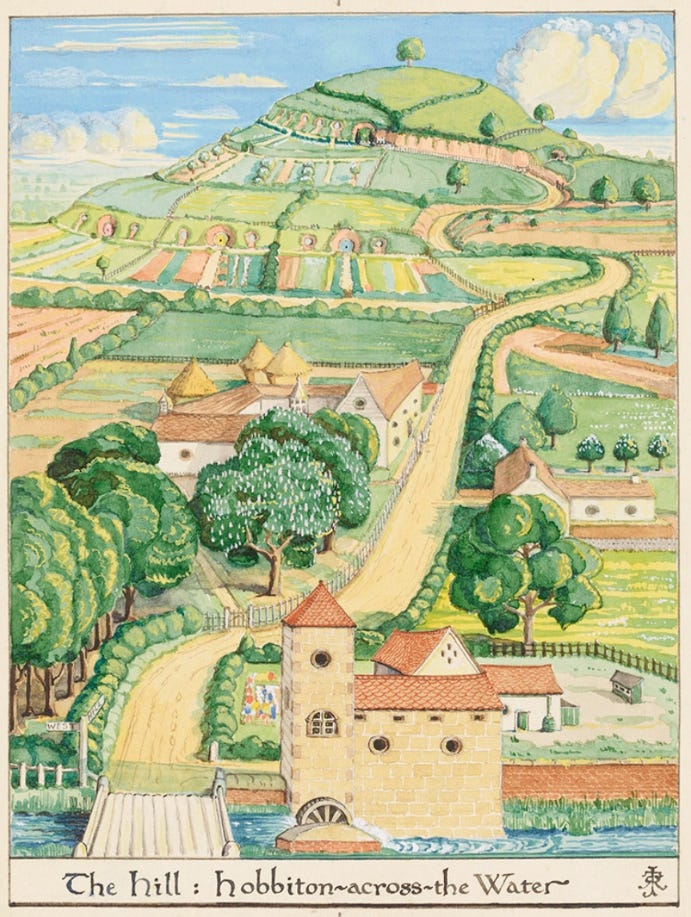

When Bilbo Baggins completed his book, he titled it There and Back Again. A fitting title, not just for Bilbo’s journey, but for life itself. We are called to return to our origins—the fertile ground of home where we plant the seeds of virtue. Home is also where our moral acts are tested—whether they were ostentatious or truly grounded in goodness. As the Sufi teaches, “Worship done for ostentation is submerged in the earth, but that which is done for God’s sake ascends to celestial spheres.”

Living a hidden life, filled with the simple routines of seeing smiling faces, doing good work, breaking bread, singing song, and sharing prayer, is a direct action against the global monoculture. Countless poets and sages praise the hidden life. Seeking the grandiose and deluding ourselves that we can make history, on the contrary, is a folly sold to us by a culture that consumes itself, and the planet.

This emptiness mirrors the broader cultural narrative of seeking grandeur to fill a spiritual void. It is no coincidence that at the turn of the twentieth century, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, founder of Italy’s Futurist Movement, glorified violence and destruction as paths to immortality. He asserted, “We will glorify war—the world’s only hygiene—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman. We want to demolish museums and libraries, fight morality, feminism and all opportunist and utilitarian cowardice.” This impulse is woven into our stories, myths, literature, and film, perpetuating the allure of spectacle and destruction. Just recently, the world witnessed a young man publicly execute the CEO of a health insurance company in the United States as an act of vigilante justice.

Modern man seeks the grandiose. Perhaps it may not lead to acts of violence, but it leads to a delusion of grandeur, and the rise of social media, where people are called to share the extravagant, is a testament to this. Our activism and community organizing often follow this same pattern. Events must be grand, movements must go viral, and voices must be amplified on public stages. While these efforts can be powerful, they risk losing the quiet, meaningful work that sustain communities.

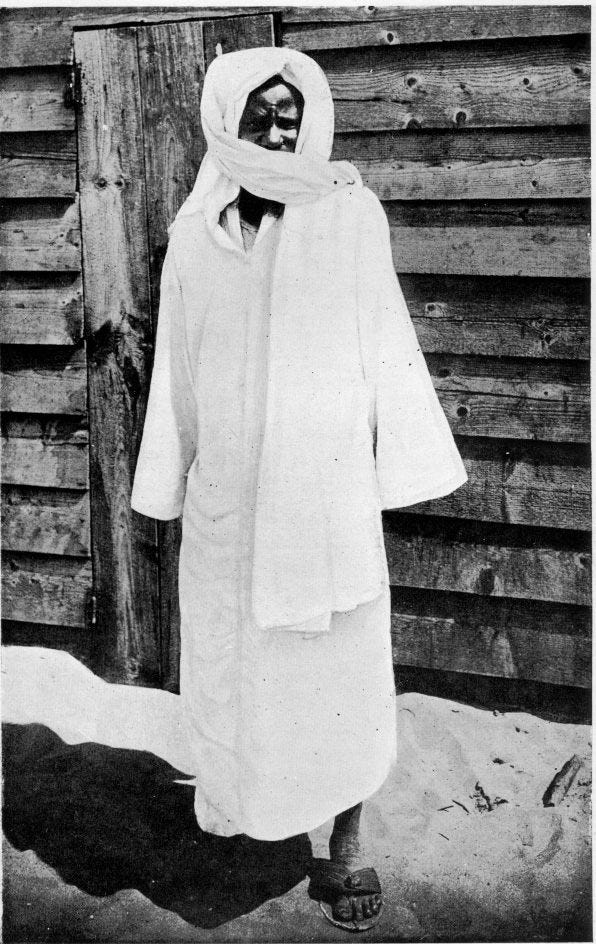

That quiet, meaningful work lasts generations, and the testament is found all over the world. In the 19th century, the great Senegalese Warrior-Saint, Shaykh Amadou Bamba, is said to have taught his disciples, during the brutal French occupation, to focus on building community through small-scale agriculture, regular communal worship, community schoolhouses, and trust in God.1 For over a century, disciples have continued to preserve Shaykh Amadou Bamba’s Legacy—a legacy that didn't make noise but rather built men and women of God.

It is those small acts that live on. A regular meeting between friends, family dinners, reading circles, choirs, etc. These are the lifeblood of goodness. The Great Sufis, just like the Hobbits remind us of what William Wordsworth called “the best portion of a good man's life: his little, nameless, unremembered acts of kindness and love.” They are anti-industry, par excellence. In Tolkien’s world, their courage lies not in seeking greatness but in living simple, grounded lives. As Gandalf says, “It is the small everyday deeds of ordinary folk that keep the darkness at bay.” In a world obsessed with being remembered, perhaps the true heroism lies in remembering those who are forgotten: the elders, the orphans, the sick. A good life needs no image or public validation—only quiet service and love.

Cochrane, Laura L. "Addressing Drought through Rural Religious Communities in Senegal." Africa, vol. 90, no. 2, 2020, pp. 339–356. Cambridge University Press. Accessed January 5, 2025.

Beautiful. As the aged Bilbo remarks, “It is no bad thing to celebrate a simple life.”

Thank you 🙏🏼