#Seed033: Spiritual Wisdom, Ecological Design and Living Systems

Exploring the Spirituality of Ibn al-Arabi & the Timeless Way of Design

Consult the Genius of the Place in all,

That tells the Waters or to rise, or fall.

- Alexander Pope

In the late-1970s, an architect by the name of Christopher Alexander came to see a pattern, so obvious that it had never really been articulated before. Christopher Alexander saw that good design has patterns that can be read and articulated, a language of sorts. He also explained that all these languages had a particular quality, which he called the Timeless Way, that quality that we all know but has no name. Alexander wrote that the Timeless Way “is a process which brings order out of nothing but ourselves; it cannot be attained, but it will happen of its accord, if we will only let it.” It is that universal experience of entering a building, a town, a garden, a temple, a forest, or a living room, which makes you feel the quality with no name. This universal quality is something we all recognize, even if it eludes precise articulation. This is the reason we like quaint small towns with a main street and the souks of the maghrib while we find the suburban strip malls or the mega-mosque so distasteful and dull.

A pattern language is an attempt to articulate the Timeless Way. For Alexander, the role of the designer of gardens, homes, towns, and communities is to capture the Timeless Way. How might we as designers, that is to say as gardeners, educators, architects, artists, craftspeople, community organizers, and so forth, tap into the Timeless Way? To answer this question, I invite you to turn inwards. As you read on, I encourage you to reflect on your own designs—whether in the garden, at home, or in your community—and consider how they embody these timeless principles. What are those qualities, within, that make us into witnesses of beauty, goodness, and truth? In this piece, I'll explore how the Great Sufi mystic, Ibn al-Arabi and his moment of enlightenment can help designers not only deepen their relationship with the world around them, but become designers who are aligned with the Timeless Way.

The Divine Qualities & the Timeless Way

The Timeless Way captures a facet of the human experience that characterizes an enlightened person. In our lives, there are moments when we experience enlightenment. When we fall in love, when we complete a work of art, or perhaps when we listen to a beautiful song, all these are glimpses of the eternal. We could say that these are moments when we are closest to the True, the Good, and the Beautiful. In the Islamic tradition, there have been countless men and women who befriended God, that is those Absolute Qualities. Fortunately, Ibn al-Arabi documented his path to sainthood, to such detail, that we can truly see what it's like to traverse on the Timeless Way. In that, we can truly benefit from this blueprint.

In the first chapter of the Meccan Openings, Ibn al-Arabi describes the climax of his enlightenment as he was circling the Ka’aba.1 Nestled in the Ka’aba, we find the black stone, which is said to symbolize the Hand of God. Pilgrims are called to kiss the black stone, as they enter the circular trance-like state in the holy precinct. Ibn al-Arabi shares his experience as he reaches to kiss the Hand of God. Each attempt to kiss the black stone is halted by a direct experience of one of those Divine Names. As he began circling the Ka'aba, he recalls,

“God extended His hand for me to kiss, and I accepted it, receiving the form I had passionately loved. He manifested Himself before me as the Ever-Living (Al-Hayy), and I received Him with my lifelessness. As I sought to kiss the stone, the Ever-Living said to me: "You have not conducted yourself properly," and withdrew His hand from me, saying: "I do not recognize you in the visible world as you once were."

Then, He turned to me as the All-Seeing (Al-Basīr), and I turned to Him in the form of blindness. This occurred after a period of reflection, as if breaking a condition. I again sought to kiss the stone, but the All-Seeing repeated the same statement.

Then He manifested as the All-Knowing (Al-’Alīm), while I approached Him in utter ignorance. Once again, I sought to kiss the stone and was once again rejected.

He next took on the form of the All-Hearing (As-Samī'), while I approached with deafness. I sought to kiss the stone and once again, my union with the All-Hearing was concealed.

He then manifested Himself as the Divine Speech (Al-Mutakāllim), and I approached him with my silence, unable to respond. I sought to kiss the stone, and He sent a letter, revealing the lines and inscriptions of the Tablet.

He then manifested as Divine Will (Al-Murīd),and I approached in my uttermost limited form. I again sought to kiss the stone, and He poured His radiance and light between us.

Finally, He manifested Himself as the All-Powerful (Al-Qadīr) while I became the embraced of weakness and neediness. I sought to embrace the stone again, but He made me fail my attempt.

Seeing how I was constantly turned away and unable to kiss the stone, I asked: ‘You did not reject me, nor did You fulfill me. Why?’ He replied: ‘You rejected yourself, My seeker. Had you kissed the stone at every turn, O pilgrim, you would have accepted these blessed manifestations.’”2

At the brink of enlightenment, the pilgrim found himself at a crossroads between effacement (what the Sufis call fanā’) and subsistence (or baqā’). Approaching the Divine Reality, his intuition led him to believe that he must efface himself, and adopt the opposing quality (e.g. there is no living except The Living). What was asked of him, however, was to take on the Divine Qualities. Enlightenment required him to take on the qualities of life, sight, knowledge, hearing, speech, will, and power, all the while recognizing that these are contingent upon the Absolute. This is the quintessential teaching of Sufism of “embodying the Divine Attributes.”3 The spiritual path is about embodying those attributes, and Christopher Alexander’s description of the Timeless Way is inherently spiritual. We as designers can also embody these attributes in our work.

The Design Principles of the Timeless Way

Accomplished artists, craftsmen, architects, and community organizers embody Divine Attributes. In doing so, they tread the path of the Timeless Way. At their core, they are good designers. Specifically, designing according to the Timeless Way bears such a similarity to Ibn al-Arabi’s experience at the Ka'aba that we derive seven design principles. Moreover, the seven attributes, in this particular order, prepare the designer to deepen his or her relationship to the world.

Principle #1: Life

I am living and I am part of a living world, that is interconnected in ways beyond what I can know through my five senses.

Christopher Alexander's central concept, "the quality without a name," is the essence that makes a place come alive. Alexander argues that when a building, a town, or a room posseses this quality, it feels alive and vibrant, akin to the spiritual understanding that life is an intrinsic and fundamental attribute of the Divine.

Ecological design, biomimicry, permaculture, and circular economics are just a few of the life-affirming practices and philosophies used by contemporary designers. Permaculture farms, like Geoff Lawton’ Zaytuna Farm in Australia, illustrate life-affirming design by demonstrating how humans can interact with ecosystems while regenerating them. At its core, life as a design principle takes a systems approach and recognizes the the whole is more than the sum of its parts. Instead of approaching the cosmos as lifeless and separate, we recognize ourselves deeply woven in the cosmic web.

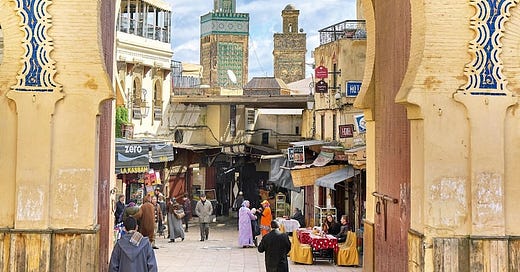

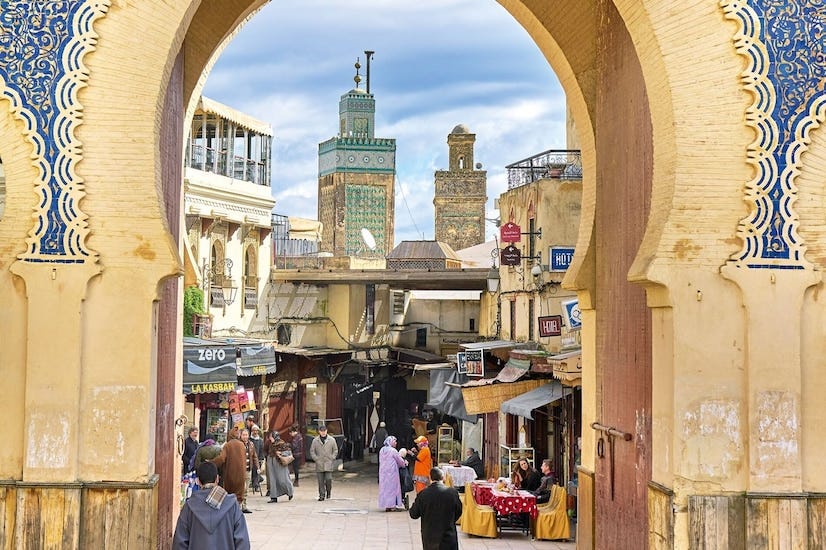

The great cities of old, often built from generations to the next, were at once wild and orderly, generations of infrastructure built on top of each other, like an old forest. There were no megalomaniac planners trying to build a Cartesian grid, but rather beauty was etched in the simple arches, alleyways, houses, and temples. I can think of no greater remaining example than the City of Fez in Morocco. Titus Burckhardt writes in Fez City of Saints, “if one should escape from the throng of the bazaars, and enter one of the high, narrow, ravine-like streets, above which the heavens peep down between the high black walls of houses, and where, in the half-light, a few people are passing a woman, perhaps, wrapped up in white flowing garments, grave-faced men or a beautiful child-one encounters the cool, fine breath of ephemerality, which belongs to every truly Islamic city. Everywhere, in the midst of sound buildings, there are ruins, which no one takes amiss, for death belongs to life; even new buildings seem, under their white lime plaster, to be timeless.”4

Principle #2: Sight

I see how parts of the world form a whole.

I wrote earlier about the first permaculture principle of observe and interact. Sight is related to the ability to perceive the whole rather than just the parts. We are participating in a living system, and our first encounter is the visible realm. The Timeless Way asks of designers to see the overall pattern and how elements fit together. That said, sight isn't only about the seeing through the eyes. Inner sight, through the eyes of the heart, helps us see what truly matters, or rather things as they are.

Bad design is usually caused by a lack of foresight into the future or designing in isolation of the whole. Anyone who has walked in a gentrified neighborhood will have witnessed cookie cutter buildings that seem out of place. Gardeners who excel at their craft will look at their landscape and understand not just seasonal patterns but future growth. A designer with a "divine sight" sees the interconnectedness of all parts of a space and how they contribute to the life of the whole, mirroring the divine attribute of seeing all creation as an integrated whole.

In One Straw Revolution, Masanobu Fukuoka writes, “observe Nature thoughtfully rather than labour thoughtlessly.” As designers, especially who recognize their work within a much larger space-time continuum, then you are working with, rather than against nature. It seems to be a modern trend, to design and build for a quick profit, not thinking of the impact, or lack thereof, that the design will have on ecosystems and future generations to come.

Principle #3: Knowledge

What I know is more than what I've read or what I've been told, but rather what I have tasted and experienced.

Knowledge and information are not synonymous. The most beautiful gardens and towns were not necessarily designed by experts, but rather by people who could read and articulate pattern languages.

Patterns are derived from a deep understanding of human experience and natural processes. To know these patterns and to be able to interpret requires knowledge of human nature, which is a form of sapiential, that is to say, experiential knowledge. Davis Homes is a housing project from the 1970s that captures this insight. A well-designed community integrates the human experience in ways that are often subtle and unnoticed by the observer. An intentional community has design patterns that allow for the flow of life to run through it.

Principle #4: Hearing

The cosmos is harmonious and what my work strives to be in harmony with the inner and outer reality.

Hearing is about being attuned to the context in which one designs. Alexander emphasizes the importance of listening to the site, the materials, and the needs of the inhabitants. A designer must be sensitive and receptive to the environment, listening and understanding to the needs to the place to create something that truly belongs and fits harmoniously within the whole.

A natural ecological garden tends to fit harmoniously within the whole, by design. Moreover, adopting permaculture principles looks at stacking functions, which would beg the question: how can we simultaneously design gardens that fit within an ecosystem while feeding us? The answer is usually found in various forms of food forests, and other edible perrenials. David Holmgren’s property in Australia is a perfect example.

Principle #5: Speech

Everything in the cosmos speaks a language.

Design communicates meaning, function, and beauty. Language of patterns convey deep truths about the human experience. Designers must ask themselves the question, what is my design communicating?

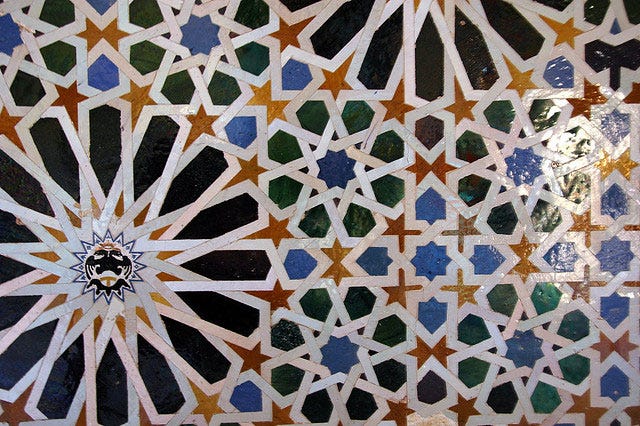

The geometric patterns of Alhambra communicate the interconnectedness of the cosmos. There is an otherworldly experience of the geometry, connecting the human soul to another realm. Just as the artist attempts to convey a message, all design conveys a message and meaning about the world. As designers, we must reflect deeply on what speech our work is meant to convey.

Principle #6: Will

The canvas of the designer is possibility.

Will is reflected in the intention behind design choices. A designer’s role is to will a space into being that reflects the above principles. The designer must accept his or her place as designer. Once the aforementioned principles have been adopted, then the designer is ready to create their design. Designing a garden, for examples, would mean putting pen to paper to drawing it out. A community organizer may prepare a strategic document or concept note highlighting the mission and vision for their work. The point here is to clearly define the intention.

Underlying the principle of will is proper planning. A design is theoretical until an execution plan is developed. A designer must assess the tools and techniques needed to implement the design, and organize a team of people who can bring it all to fruition.

Principle #7: Power

The actualization of possibilities.

This is the actual creation and manifestation of the design. Designer must harness their own power to bring their work to life. In some cases, this takes a team of skilled workers. A community organizer may need someone to project manage, fundraise, campaign, draft legal contracts, manage resources, etc. A gardener may need a carpenter, a soil scientist, a landscaper, and so forth. This Canadian farm house is beautiful, simple, and elegant design that incorporates all seven principles mentioned above and brings everything to life.

I was fortunate to do an in-depth, line-by-line, study of the Meccan Openings with my friend and Sufi teacher, Shaykh Hamdi Ben Aissa. As we were reading and reflecting on these passages, it became increasingly clear that studying the works Ibn al-Arabi is necessary to confront the metacrisis. I suggest you take a look at some of the recordings on his website. It brings me nothing but joy and relief to see other teachers around the world such as Dr. Ali Hussain, Shaykh Muhammad Adeyinka Mendes, and Dr. Hasan Spiker exposing Ibn al-Arabi to countless people, especially among younger generations of seekers, all over the world.

Ibn Arabi, Muhyiddin. Al-Futuhat al-Makkiyah. Edited by Abd al-Aziz Sultan al-Mansub, vol. 1, Sana, Yemen, 2010, pp. 171-172. (my translation)

تخلّق بأخلاق الله: Though not a direct saying of the Prophet Muhammad, the idea can be traced to sayings and teachings of Sufi scholars and philosophers who emphasize the importance of developing a noble character by reflecting God's attributes in one's actions. One influential figure often linked to these teachings is Al-Ghazali (1058–1111), who wrote extensively on ethics and spiritual purification. In his works, he stresses the importance of imitating divine attributes as part of the path to closeness to God. Additionally, sayings attributed to early Sufi masters like al-Junayd and Rabi'a al-Adawiyya often emphasize the need to align human behavior with divine ethics.

Titus Burckhardt, Fez City of Saints (London: Islamic Texts Society, 1992), p. 79.